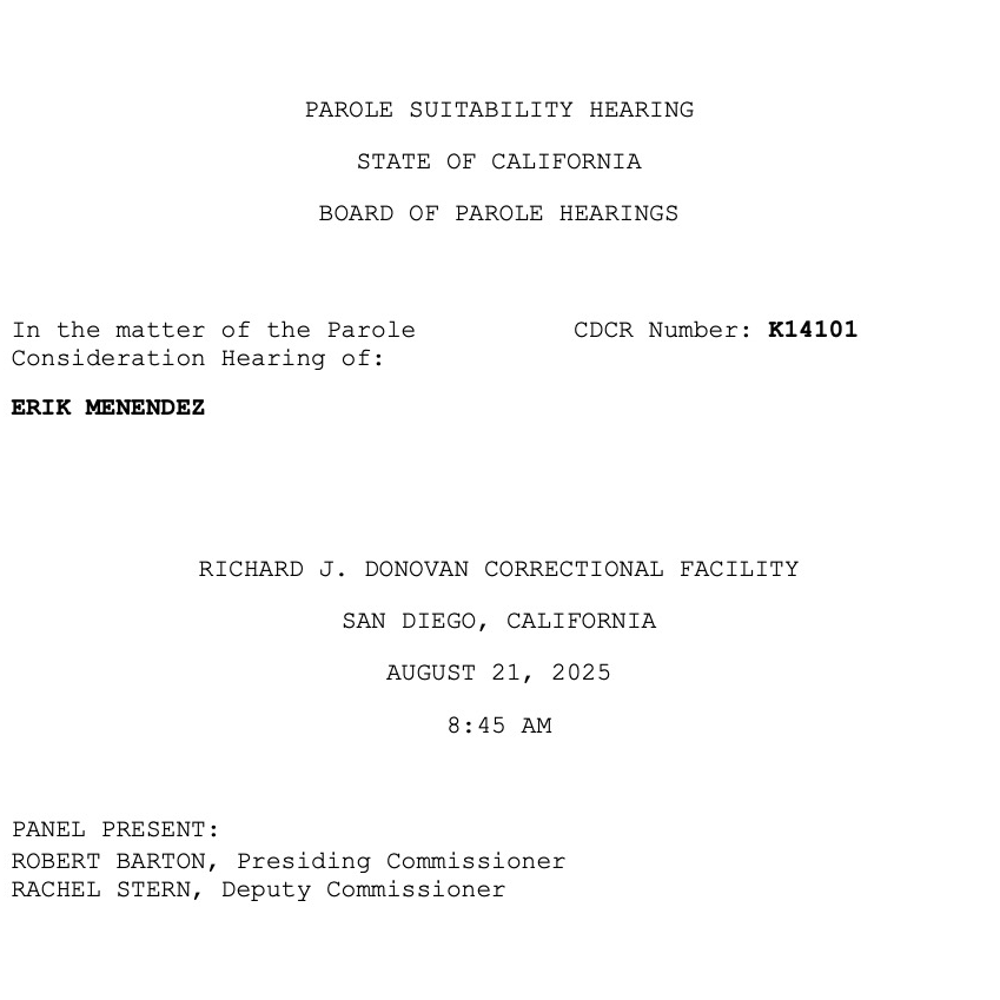

Both Erik and Lyle Menendez were DENIED PAROLE – they were found “unsuitable for parole” – at hearings August 21 and 22 – days after the 36-year August 20 anniversary of the killing of their parents, Jose and Kitty.

Erik’s hearing was ten hours long. Lyle’s hearing, the next day, lasted 11, while he average parole hearing in California lasts two or three.

On both days there were no lunch breaks – only a series of ten-minute bathroom breaks. James Queally from the Los Angeles Times wrote pool reports that the members of the official media pool – which included me – received in real time.

We were NOT allowed to print, post, or broadcast any details until the two parole commissioners – two different ones for each day – announced their final decision.

Until today, we only had the pool reports to fill us in on information from what happened each day.

In the past two weeks, I’ve done dozens of interviews with multiple sources about what actually took place during the parole hearings.

The complete transcripts from the hearings are scheduled to be released in two weeks.

A major controversy erupted late in the afternoon of August 22, during Lyle’s hearing, when Commissioner Julia Garland announced that there had been some type of “audio leak” of Erik’s hearing from the previous day to ABC 7 in L.A.

Initially, Ms. Garland said, “the audio of the entire hearing had been leaked” to the TV station. Ten minutes later, the commissioner came back after a recess and announced that “only a few sound bites” had been sent by the CDCR to ABC 7 following a “public records request.”

What followed over the next 90 minutes can only be described as a complete and total meltdown – like a scene out of a movie – much more serious than was revealed in the pool reports.

One of the Menendez and Andersen relatives was yelling at the commissioners.

Others said they were not going to read their statements because they felt “unsafe about the integrity of the hearing” and were “worried that the audio of the confidential hearings which included their personal statements” would be leaked out.

Jose’s sister, 85-year-old Terry Baralt, who is being treated for lung cancer, wept openly as she told Lyle, “she loved him and wanted to see him come home soon.”

Menendez parole attorney Heidi Rummel made a passionate argument saying she thought “the rest of Lyle’s hearing should be continued and that the parole commissioners should not announce any decision for Lyle that day” since she planned to file papers with an appeal court about the situation.

There were a series of shorts breaks followed by brief, in-session, back on the record segments over the next 90 minutes. The commissioners initially were apparently unsure of how to proceed.

Finally, the parole commissioners did announce a decision to DENY parole for Lyle Menendez just before 8 pm after their last break in a 11 hour hearing over the objection of Menendez attorney Heidi Rummel.

I’m going to share a series of commentary and analysis posts in the coming days to report details from the grueling marathon two days ofhearings. This first post will answer the two questions I’m asked most frequently in media interviews:

- Erik and Lyle Menendez were 18 and 21 years old and nationally ranked, competitive tennis players. Why didn’t they simply walk out the front door if they were in fear for their lives?

- Maybe I’m willing to accept that Jose Menendez was a monster who sexually abused his sons. But why did they kill their mother Kitty? Aren’t all mothers loving, caring, and nurturing?

Erik’s lead defense attorney Leslie Abramson had a line in her closing argument where half of the members of each of the two juries voted for manslaughter, not murder.

“Jose and Kitty Menendez ran boot camp Beverly Hills,” she said. “Kitty was one of the guards, not one of the prisoners.”

[HEARING TRANSCRIPT EXCERPTS]...

ERIK MENENDEZ: Lyle was living at home during the summer of the burglaries. Uh, and then he went off to Princeton that fall, and he would be home on and off. He was constantly flying home. Uh, so, he was home periodically. He lived in the guest house.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. So, on and off during that whole year.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Right.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: And when did the two of you, or did the two of you first discuss doing something to your father and mother, or father?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I went to him the Tuesday before to tell him what was — I didn’t go to him specifically to tell him. I had seen an incident with my mother in the foyer, uh, with my brother. And so, I went to the guest house, and I just broke down and started telling him. Uh, but there was no talk about doing anything to my parents. The talk was, “You’re coming back to Princeton with me.” I told him that the — the — the sexual violence was still going on, and he was very upset. He — he was very angry at me, and, uh, I think he felt very guilty. But he, uh, he — he believed that I would be able to go back to Princeton with him, and that he was gonna take me away from it and end it. It’s when that did not work, and his confrontation with dad turned very bad on Thursday night that, uh, that was the first talk of buying guns. But the buying guns — the talk of the buying guns was not, “Let’s buy guns and kill them.” That wasn’t the conversation. Uh, the talk of buying guns was because now it had become, uh, very dangerous, and I had broken the one rule that my father told me never to break. So, uh, and that’s —

Now, onto the second question:

Why did Lyle and Erik kill their mother Kitty Menendez?

This question has always been the focus of prosecutors going back to the first Menendez prosecution in 1993-94 that ended with two mistrials.

Half of the first trial jurors – mostly the women – voted for manslaughter, not murder. The brothers would have served 22 years in state prison if they’d been convicted of manslaughter. Instead, they’ve been incarcerated for 35 years and five months.

This is what Erik answered in his parole hearing:

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: — at the time, you’re gonna go kill dad as preemptive. Right?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, you had never told Lyle before that that you were being sexually abused?

ERIK MENENDEZ: No.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: And you had never talked to him about his sexual abuse of you at that point?

ERIK MENENDEZ: No. Lyle and I never discussed that until —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You said in court he apologized for something.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Exactly.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, while you were in county jail during the trial, did you have that discussion?

ERIK MENENDEZ: No, not until after he was on the stand.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Were you suppressing that, or did you think he didn’t remember it, or you just didn’t wanna talk about it?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I didn’t wanna talk about it. Lyle and I were raised purposely to — to not talk to each other about emotional or — or — or traumatic things. We just were not — we were raised to keep that inside, that — that talking about something like that was considered a great weakness. And, uh, the shame of what he did to me, there was — I couldn’t imagine bringing it up to him.

ERIK MENENDEZ: I didn’t wanna talk about it. Lyle and I were raised purposely to — to not talk to each other about emotional or — or — or traumatic things. We just were not — we were raised to keep that inside, that — that talking about something like that was considered a great weakness. And, uh, the shame of what he did to me, there was — I couldn’t imagine bringing it up to him.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, when you talked about getting the guns, what was the purpose, if not to use them?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I — I — the purpose was to use them if my dad — when I — when we — when we talked about getting the guns, I had made the decision I was never going to let dad come in my room and do that again. That was never going to happen. And now, Lyle, I had — I had — Lyle was my ally, and, uh, Lyle had wanted to run away. He wanted to leave, go somewhere, talk to someone, do something, and I told him that that was impossible. And so, the decision —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, stop. Why? Why would you tell him that?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Because in my mind, leaving meant death. There was — there was no consideration. I — I was — I was totally convinced that there was no place I could go. It was not a consideration to me. It didn’t matter where I was.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, you were — you were 18, right?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You know at you can leave home. People do it all the time, especially in bad situations.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes. Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You had family members, in fact, some of them are here, that would’ve taken you in. Right?

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You had family members, in fact, some of them are here, that would’ve taken you in. Right?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You had your brother now who was saying, “Let’s leave. Let’s get out of here.”

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: And so, there wasn’t any part of you, you don’t think, that was thinking, “I’m gonna end this my way by killing him,”? Because you kind of put yourself in that position.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Right. Right. It’s difficult to convey, uh, but I’m gonna try, uh, how terrifying my father was. The idea that — that I could walk into a room and shoot him was inconceivable to me. I — I fantasized about him not being alive when I was a teenager. But the idea of me pulling a trigger and killing him? My dad was the most terrifying human being I’ve ever met. He still is.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. But wait a minute. You’re — you’re — you’re shifting the question. My question was, if you had these opportunities and people basically telling you, your brother, “Hey, let’s just leave,” and the alternative is, “I’m gonna get a gun knowing that he’s gonna come at me again, and I’m gonna shoot him,” in self-defense or whatever, versus, “I’m gonna leave, go to the authorities, go to family, go to whoever. I’ve already disclosed to Lyle. Let’s just leave so I can get away from this monster.” Why didn’t you make that choice? What kept you in the house?

ERIK MENENDEZ: My absolute belief that I could not get away. It sounds — maybe it sounds completely irrational and unreasonable today, but at the time, there was — I was —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, I’ve dealt with a lot of sexual assault victims, and I get that learned helplessness. I understand the syndrome. I didn’t need the psychologist to write me and explain it. I’ve seen it. So, I understand that. But also, oftentimes, those people that have no other options, in other words, if they were to leave, they’d literally be homeless with nothing. You weren’t in that situation. You’re a smart guy. At that point, you had, what, a 4.or something in high school?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I wish. Uh, uh, a 3.1.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. Still —

ERIK MENENDEZ: But I was still smart.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Still could have gone to college.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Even if it was a junior college, you could have gotten a job. Right? It would’ve meant the end of your tennis, would’ve meant the end of your lifestyle, and that’s one of the things that I’m curious about too. Because in your writings you say there is, I quoted it, “I have no justification for what I did.”

ERIK MENENDEZ: Right.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: And — and that’s your belief today, correct?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Correct.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Was there any part of this that you believe was self-defense?

ERIK MENENDEZ: No.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: No. There was no imminent — I mean, I get it if he’s pounding, coming through your door. But you’re basically —

ATTORNEY RUMMEL: I’m gonna object to him making legal conclusions, because we have a pending habeas. There’s an order to show cause in the habeas. His mindset, his beliefs, his fears is — is what’s relevant here, not his legal —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, counsel, you should — you should then advise him not to answer the question before he answers it. So, I — I’m not asking him for a legal conclusion. I was asking him about the statement that he said, “I have no justification for what I did.” He actually wrote that.

ATTORNEY RUMMEL: Are we asking about self-defense and perfect self-defense. If we’re gonna go down a legal analysis pathway (inaudible) —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: No, I’m not asking him for a legal analysis, and I think he understood the question.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yeah. I — I —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: The point of the question was what — ’cause he was telling me, or I — or you were telling me, Mr. Menendez, about this fear and that you had got the guns not to kill them. And I said, “Why’d you get ’em?” And then, you digressed. You didn’t really answer. You said, “I’m not gonna –”

ATTORNEY RUMMEL: I’m gonna —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: “I wasn’t gonna ever let him do that to me again.”

ATTORNEY RUMMEL: I’m — I’m gonna object again. I — because the com — uh, the Panel cut him off when he was talking about his father and his fear of his father, which is the ex — is the answer to that question, and — and he wasn’t allowed to finish that discussion. But — but his mindset is — is the — the — the basis for his choices. And I — I think he needs to —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, I’ll go back —

ATTORNEY RUMMEL: — a full opportunity to answer.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: I appreciate your — I appreciate your objection. It’s not really an objection. It’s just a comment on what I was saying. But as far as you, Mr. Menendez, I’ll ask the question again. What was your purpose in getting the guns?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Uh, I — I will — I will, uh, I assume we’ll get to the night of August 20th, and I — and —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Yep.

ERIK MENENDEZ: — we’ll — okay.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: We’re about there.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Uh, okay. Uh, my purpose in getting the guns was to protect myself in case my father or my mother, uh, came at me to kill me, uh, or my father came in the room, uh, to rape me. That is why I bought the guns.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. And how many guns were purchased?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Two.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Why was that?

ERIK MENENDEZ: One for me and one for Lyle.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, Lyle, you believed, was going to assist you or was going to help you in some way if you were attacked?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes. Uh, but he — he — telling – – telling Lyle and exposing the family secrets, and my dad believing that we were gonna go and tell other people, meant that our lives were in extreme danger immediately. So, Lyle did not feel comfortable. If I — if I wasn’t leaving, he wanted to have a gun.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. So, why use fake ID to get those guns?

ERIK MENENDEZ: That was the — it was the ID I had on me. I didn’t have an ID. And two, even if I had an ID, I wouldn’t have used it. I wouldn’t have used my own driver’s license.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Why?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Uh, because on Friday, we didn’t have an intention to kill, uh, my parents. And if we buy the guns, and I have my ID, and I put my — my address, then paperwork’s gonna show up at the house. My parents are gonna know I went and bought guns on Friday. We — we were trying to conceal that.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. Had you bought guns before?

ERIK MENENDEZ: No.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: How do you know paperwork would show up at the house?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I’m just assuming that brochures, whatever will show up at the house.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. So, you go back home, and you see the interaction between your parents, and they go in the den. Was it your idea then, or Lyle’s? Who — who first acted in terms of the violence?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Lyle came to the top of the stairs after my dad had ordered me to my room and said he was coming up, uh, and — and said, “It’s happening now.” But I — my focus was, “Dad’s coming to my room. I can’t let dad come to my room.” Uh, and Lyle said, “You understand it’s happening now.” And — and I knew what that meant, and we were about to die now. And I told him, “My gun’s in my room,” and I ran to my room to get the gun. All I knew was that I gotta get to that den. Fear was driving me to that den, uh, and — and rage. Uh, the idea that dad was gonna come to my room — dad was going to come to my room and — and rape me that night. That was going to happen one way or another. If he was alive or — or that was going to happen. And so, I just — I went, and I ran, and I got the gun in my room, and I went down to the car, and I loaded it, and I ran into that — that den before Lyle could. Without — without a discussion, before Lyle. I didn’t even wait for Lyle. I knew I had to get to that den.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. But again, from an outside objective, I get it. Not thinking straight. You had the trauma, all of that. But you do see that there were other choices at that point.

ERIK MENENDEZ: I get that. Looking back as a healthy individual today, that there were obviously o — other choices. When I look back as — at the 18-year-old that I was, and I don’t mean to minimize it by saying I was 18, just the person I was then, uh, and what I believed about the world and my parents, running away was inconceivable. Running away meant death. There — that was never going to happen. It wouldn’t matter where I was. My father sent me on tennis trips when I was 12. He didn’t think that I was gonna tell anybody or run away. He had no fear of that. He had trained me to believe that — that running away meant death. I knew it. And so, at that car, it’s logical. I get it. I’m at the car. Why didn’t I get in the car and drive away? I understand that question.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: And you had a shotgun.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Uh, right. It — it was inconceivable to run away. You would have to live my experience to understand that there was no way I was running away, and if my dad exited that den before I got to that den, I was dead.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. So —

ERIK MENENDEZ: That’s what I believed. I believed it.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: — at the time, you’re gonna go kill dad as preemptive. Right? Uh, ’cause you’re — you had this fear. Why kill mom?

ERIK MENENDEZ: I — I saw my mom when — when my mom told me on Thursday that she had known all of those years, it was the most devastating moment in my entire life. It changed everything for me, and it — it changed the way I — I had been protecting her by not telling her. When she told me on Thursday that she knew I saw her and dad, my — my mom, all my life had been my dad’s ally, telling my dad everything that I did wrong, getting my — getting — watching me get whipped in front of her. But I still believe —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Do you still think so, or — or have you rethought that?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Rethought which part?

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, whether she was his ally. What if she was his victim?

ERIK MENENDEZ: She was his victim. She was definitely his victim. And a lot of what she did and blaming me was — was to avoid her getting hit. When my dad would beat my mom, and I would see blood on the sheets the next morning, I knew it was because of me. He was beating her because I failed. She was his victim.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: You wrote about all that too. Again, I’m not trying to have you revisit it. I’m trying to figure out that night, why, if — if you — if you knew that this was happening to your mom, I get the betrayal that she knew, and you thought you were protecting her by not telling her, but she knew. Still, if you have this burning hatred towards your dad, you had no thought about rescuing your mom at all?

ERIK MENENDEZ: What — a series of incidents told me that my mom would not just not take our side, but egg him on. When we — when I found one of my mom’s suicide notes, and I called my brother and said, “Mom’s going to commit suicide. We need to — we need to do something,” my brother had gone to my mom. This was a few years before, and said, “Leave dad. We’ll leave with you. We’ll go back to New Jersey.” And my mom said, “I’m never leaving your father. Your father is a great man, and I’m his wife, and that’s — that’s who I am.” It — it — through step by step, my mother had shown, uh, uh, that she was united with my dad, but I still didn’t believe she knew. And when I found out that she knew, I no longer saw him and her as different. They were different. She was his victim. I should have known that. I should have — I should have — I should have separated it in my mind. But at — but at that night, I — I saw them as one person. Had she not been in the room, maybe it would’ve been different. It would’ve been different, but —

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, but wait a minute. I’m going to ask you about that. Because when you shot him the first time, she was still alive. You had to go out and reload to kill her.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes. Yes. All — all I heard was – –

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So —

ERIK MENENDEZ: — was a — was a — was a, “No.” And — and — and I — and I ran out. Uh, uh, that — that’s — that’s the, uh, that’s — that’s the part of this that is the — is the hardest, and — and you’re right. Um, I — I wish to God I did not — I did not do that.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, so, after the murders — are you doing okay? You need a break?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yeah. No, no, that’s fine.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Well, you’re not fine. No one would be fine after discussing this. Take some deep breaths. Like I said, don’t hold your breath. I don’t want you passing out in there.

ERIK MENENDEZ: Okay.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, after the murders, you — and I’ve read what you wrote. It wasn’t immediate but then you realized police weren’t coming, and you were gonna figure out a way to cover it up. Right?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: So, did it ever occur to you that maybe you’re putting other people in danger by just disposing of guns?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Not at that time, no.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Where’d you dump ’em?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Off of Mulholland Highway.

PRESIDING COMMISSIONER BARTON: Okay. Chance anybody could find them, right?

ERIK MENENDEZ: Yes.

COMPLETE OFFICIAL TRANSCRIPT:

ERIKMenendez, K14101, 2025-08-21 corrected

More like this?

Get the book!