Lyle Menendez Parole Hearing

Lyle Menendez Parole Hearing

(From Friday 8.22.25)

Complete Unedited Media Pool Reports

Via James Queally

LA Times

Posted 8.26.25

1. 9:03 am – 8.22.25

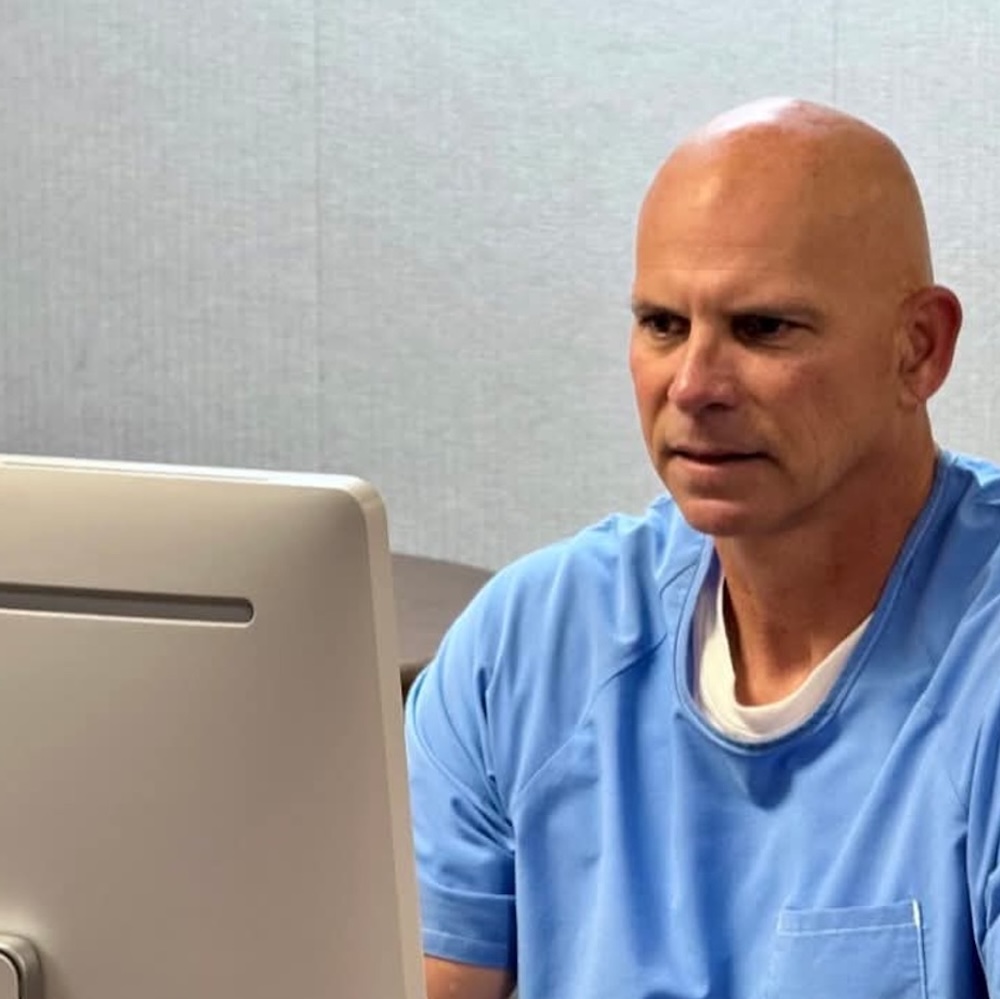

8:39 a.m. Lyle is present for the hearing, seated in a light blue jumper in a chair at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego.

Roll Call: Parole Commissioner Julie Garland, Deputy Parole Commissioner Patrick Reardon, L.A. County Deputy Dist. Atty. Ethan Millius, Heidi Rummel (Lyle’s parole attorney)

Victims Relatives: Natascha Leonardo (Kitty’s great niece), Karen Mae Vandermolen-Copley (Kitty’s niece), Diane Hernandez (Kitty’s niece) , Tiffani Lucero Pastor (Kitty’s great niece), Tamara Lucero-Goodell (Kitty’s great niece), Anamaira Baralt (Jose’s niece), Alicia Barbour (Jose’s niece), Marta Cano Hallowell (Jose’s niece), Teresita Menendez-Baralt (Kitty’s sister), Amy H (???), Sarah Mallas (Kitty’s great niece), Syvlia Baralt (Kitty’s niece – I apologize this may need to be fact checked later, there are myriad audio issues this morning and some voices are unclear.), Brian Alan Anderson Jr. (Kitty’s nephew), Robert Pastor (Tiffani’s support person), Eileen Cano (Jose’s niece), Arnold Vandermolen (Kitty’s nephew), Erunice Bautista (support person for Arnold), Maya Emig (attorney representing Joan Vandermolen, who is Kitty’s sister), Father Ken Deasy (former pastor to Lyle Menendez, ret. Los Angeles priest, lives in Hawaii), Dr. Stuart Hart (a representative of Terry Baralt), Erik Vandermolen (Kitty’s great nephew), Miriam El-Menshawi (CDCR)

Observers: Scott Wyckoff (executive officer, Board of Parole Hearings), Andrew Mickelson-Steele (Parole Hearings Board Support), Emily Humpal (CDCR Press Office), Diana Crofts-Pelayo (Gov. Newsom’s Press Office), Sylvia Aceves (CDCR), Robert Love (CDCR), Jeffrey Elston (CDCR), James Queally (Me/LA Times/Pool Reporter), Sean Connelly (CDCR)

The hearing is beginning at approximately 9:03 a.m.

2. 10:10 am – 8.22.25

Lyle tells the commissioner he is “a little anxious,” Commissioner Garland moves to swear Lyle in.

Rummel says she has some preliminary objections. She says she has a “strenuous” objection to media presence, which she describes as a long-standing objecftion, contending that “making this a media spectacle undermines the fairness” of the process.

“I draw the panel’s attention to the family’s unanimous and strenuous objection to media presence. It undermines their dignity,” she said. “It does not protect them, and we believe it’s a violation of Marsy’s Law.”

“They desire the freedom to make statements that express their feelings, share their most intimate thoughts … without being concerned about media headlines.”

Garland says she understands Rummel’s concerns, but overrules the objection.

“This is a public proceeding and due to transparency the decision was made that media will be allowed,” Garland says, noting the event is not being live streamed.

Rummel notes the board did not ask a lot of questions about the trauma Erik suffered during Thursday’s hearing, but reiterates for Garland that he wants to speak “openly and honestly” about what drove this crime.

Rummel also objects to the comprehensive risk assessment from CDCR.

Rummel raises questions about whether or not the Board has record of a confidential report involving and incident or incidences where white power gangs asked for Lyle to be removed from a yard for not fighting back against Black and/or Latino gang members. Garland says she will work to confirm the file has been looked at, but notes she does not have questions about it. This appears to have happened in the late 90s.

D.A. has no preliminary objections.

Garland says the substantive portion of the hearing will now begin at approx 9:20 a.m.

Garland explains the factors she will review: the nature of the crime, Lyle’s growth and change while in custody, while giving weight to both his age at the time of the crime and his age now.

Garland says first part of hearing will be a discussion between Commissioners and applicants as to his suitability, followed by D.A./defense attorney’s ability to ask clarifying questions, then give closing statements, then Lyle can make a closing statement. Victim’s family members and representatives will then speak. Then deliberations. Then a decision.

“What we will not be doing is a document review, there are a lot of documents, we’re not going through them to check off certificates.”

“It’s also important that you know we will not be retrying the case, we will not be determining the validity of the defense” that was offered in court, she says.

Garland says Lyle’s documents were “clearly heartfelt, well-written, informative.” Lyle says all of the documents have been written over the past five months, in anticipation of a parole or clemency hearing.

Garland asks how the sexual abuse impacted Lyle’s decision making in his life.

“It was confusing, caused a lot of shame in me. That pretty much characterized my relationship with my father.”

Lyle says around the age of 7 or 8 there was a lot of “waiting, and not knowing when something would happen” that night, or in the bathroom, or in the car, with relation to his father, on any given day.

He said it left him in a state of “hyper vigilance.”

Lyle says he felt a “total disconnection from everybody in my life growing up,” somewhat borne from a fear that people would see the sexual abuse “in” him. He said Jose never spoke with him about the abuse after it stopped.

“I was getting pretty strong lessons about not trusting the world around me,” Lyle said.

Lyle says he was abused from age 6, to age 8. Lyle thinks it stopped because his cousin Diane told his mother.

“I think it’s related to his being concerned that I would talk to people.”

Lyle wanted to sleep in Diane’s room, she asked why, and I was specific about my father touching me.

“I’m basing this really off of her memories, more than mine, so she went and told my mother. I was already 8 and it stopped after 8, right around there.”

Lyle doesn’t know if Kitty informed Jose, but he thinks she did.

“I was the special son in my family. My brother was the castaway.”

Lyle says he got “more attention, more focus, more emphasis on performance.”

“My father just attending my practices, spending the time with me in the basement, imparting his lessons. It was just obvious if my brother and I were both on the court he was with me, directing my motions.”

“The physical abuse was focused on me because I was more important to him, I felt.”

Lyle says his father “expected greatness. He spent a lot of time talking about the lineage of the family. Lions vs. sheep. Everyone else is sheep and we come from a lion bloodline.”

“We were different. I wasn’t weak like his father. Or Erik. Or my mother. It was him and I in this bubble,” Lyle says.

Garland asks about after the abuse stopped.

“It took me a while to realize that it stopped. I think I was still worried about it for a long time … I was a little bit amazed. In my family, it was just like it didn’t happen.”

“He just never touched me in that way again. There was no discussion about it,” said Lyle, but he believed it was “always in the air between us.”

“I worried a little bit that I was going to be less loved,” says Lyle, growing emotional, a blubber in his voice, when discussing the end of the abuse, even saying he was unsure if he wanted it to stop.

“He was never harsh with me. I never got beaten for doing something wrong, so it was a devastating part of it in terms of just fear, I felt contaminated … but I felt love. So I worried a little bit about that. But I feel like my father loved me throughout my life.”

“I wanted to believe my father loved me, so in my mind I felt like he was a great man and my main way of dealing with it was that it was just a sickness that some great men have,” Lyle says. “It happened when I was a little kid, and it was over. Burying the emotions was a big thing for me.”

Lyle says his father was “very brutal with physical abuse: choking, punching, closed fists. Using a belt.”

“There was no love in it. It was just surviving that moment.”

Lyle says his “love for Erik was just a really infuriating thing, for my father.”

Lyle says taking care of Erik gave him a purpose, helped protect him from “drowning in the spiral of my own life.”

Lyle says Erik was “in trouble” by the age of 3 and 4, crying all the time, stressed, at that point “openly punished, spanked, viciously. Thrown against things. My mother would drag him down the hall. I think I realized it was the two of us.”

Lyle talks about his father making him train in tennis against older players, even adult men, in order to ramp up the difficulty.

Garland asks Lyle if he felt competitive toward Erik in any way. Lyle says not in sports, but it felt like they were competing for their parents’ affections.

Lyle told himself that his father started abusing Erik instead because he was “easy, [Jose] wanted to move on from me, he wanted to be OK.”

Lyle says he tried to rationalize the switch in abuse targets in that maybe his father didn’t want to derail Lyle’s life with the physical abuse.

Lyle says Jose started abusing Erik when Lyle was 13.

Lyle is asked about when he abused Erik. “I don’t know why I did it. I think I was just trying to release it from me,” he says.

Lyle describes “pain training” sessions that were forced by his father, where he hurt Erik in a non-sexual way but as a possible form of pain endurance. A little unclear here in the line of questioning.

Garland begins asking Lyle about his relationship with his mother. Lyle says his mother also sexually abused him. Garland notes this is not included in the comprehensive risk assessment.

Lyle lets out a long sigh. “I didn’t see it as abuse really. I just saw it as something special between my mother and I. So I don’t like to talk about it that way.”

“Today, I see it as sexual abuse. When I was 13, I felt like I was consenting and my mother was dealing with a lot and I just felt like maybe it wasn’t … it’s abusive but I never saw it that way, in the same way.”

Garland cites Lyle comments in the risk assessment report where Lyle claims Kitty called him an “accident” and said she never wanted to give birth to him.

Lyle says he may have left some detail about his mother’s sexual abuse out of interviews with doctors. He is clearly very uncomfortable talking about this. “They didn’t ask. I didn’t volunteer.”

Lyle asks for a bathroom break at 10:01 a.m.

3. 11:07 am – 8.22.25

Administrative Note: CDCR is not allowing a photo of Lyle to be distributed until the end of the hearing, as some outlets violated embargo and published the photo of Erik on Thursday morning.

Hearing:

Garland reiterates they are not making a factual determination as to whether or not the brothers were abused.

Rummel notes the board has to make a “plausibility determination” in the case, as to Lyle’s account of the crime, and she argues the abuse would be a component of that.

Garland begins to ask about Lyle’s life at Princeton. Lyle discusses an instance where he was accused of plagiarism and suspended as a result.

Garland questions Lyle about his license being suspended due to speeding violations, which Lyle said were largely the result of him not wanting to be late to practices for tennis. This happened in New Jersey.

Garland begins asking about the burglary allegations. Lyle confirms Erik was behind the first burglary and showed off what he took from a safe.

The 2nd Burglary – Lyle says Erik had it planned for three days after the first incident. Lyle says he “should have obviously told him it’s insane.”

Garland asks what his motive was. Lyle said he didn’t want his brother to go alone, or Jose to find out because Lyle got caught. Said he had “fear of Dad’s reaction, which I think would have spilled over on me for sure.”

Garland raises an issue of Lyle being “Strapped for cash” around the time of the second burglary, which Lyle flat denies. Said he had an open credit card and access to bank accounts.

Garland asks about his parents’ reaction to the burglaries. Lyle says Jose was called by the father at one of the homes that was burglarized. Jose’s reaction was “you’re a moron, and more colorful language, for getting caught, for feeling sorry for the people that got burglarized.

“As I’ve told you your whole life, the weakness is dangerous and stupid and now I have to fix it,”Jose said, according to Lyle.

Rummel and Garland are now arguing as to whether or not the trial evidence in the case has been reviewed. Garland says she doesn’t have the actual transcripts and relied on the appellate opinion. Rummel says that would have been submitted as part of the D.A.’s record.

Rummel is now questioning whether or not the board can make an accurate determination at the hearing without that evidence. Garland reiterates she is going to move forward relying on the appellate decision.

Rummel notes the risk assessment did not consider the appellate decision, only the probation officer’s report.

Lyle says any statements about him having financial problems at the time of the burglary came from his Uncle Brian, who was “opposed to our release.” Lyle says Brian’s statements were inaccurate.

“I think the best source of what was happening with me financially would be my Aunt Terry. My Uncle Brian lived in another state and didn’t know us well.”

Garland moves on to the topic of disinheritance. Lyle mentions the therapist, Dr. Oziel, was told by Jose that “they” (Lyle & Erik) were taken out of the will.

Garland asks why Lyle didn’t write about being disinherited in his submissions to the board.

Lyle says the disinheritance was not a motive for the killings, but it did become “a problem afterwards” as they feared they would have no money once their parents were dead.

“I believe there was a will that disinherited us somewhere.”

Garland asks if Lyle did go to “great lengths” to make sure a hard drive was erased with any will on it that disinherited the brothers.

Garland asks about his parents recording Erik’s phone calls. Lyle says he discovered recording equipment in the house.

“It turns out, my mother was just listening to conversations that my brother had with me.”

Garland asks if the murders were planned. Lyle says they bought the guns, which “made it more likely,” but he says he didn’t buy the guns specifically to plan his parents death.

“I thought it was de-escalating … it gave me some measure of safety.”

“There was zero planning. There was no way to know it was going to happen Sunday,” says Lyle, who now refers to buying the guns as “the biggest mistake,” but repeats that he bought them strictly for protection. “emotional protection,” he says.

Lyle says they did not discuss potentially killing their parents when they bought the guns. He said they discussed “serious threats” that Jose made “if it ever got out.” (Unclear, but presumed, that “it” refers to the sexual abuse.)

“Long guns are not very useful for protection but it was better than nothing,” Lyle says.

Garland brings up that Erik had testified “it first was discussed a week before,” meaning the murders. Lyle denies this. Rummel challenges Garland to cite directly where she’s getting that from, Garland does not immediately know where that record came from.

Rummel suggests there is an inaccuracy in the D.A.’s “statement of views” related to this point. (this is a 75-page document submitted to the parole board by the D.A.’s office ahead of the hearing. This is a public document any of you can request from the L.A. D.A.’s office if you so choose.)

“The decision to buy the guns was Thursday night, it was somewhat impulsive … and that was it. There was no other discussion,” Lyle says.

Garland asks whose idea it was to get the guns. Lyle says he doesn’t remember.

Lyle says they bought shotguns, not handguns, because there was no waiting period.

Lyle references going to a shooting range. A discussion about what ammunition to use for protection. Lyle recalls a discussion about using buckshot or birdshot.

Lyle knew there were a lot of guns in his family’s home, specifically his Dad’s bedroom. “We had just always had guns in our home. There were guns in the house.”

Lyle says he had access to “some” of those weapons but didn’t check if they were reachable the night of the murders.

Garland says she needs to review her notes. A short break is called so she can review at 10:56 a.m.

4. 12:32 pm – 8.22.25

Garland reopens discussion of when or if the murders were planned. She reads from pg. 27 of the D.A.’s statement of views, which notes that Dr. Oziel testified the murders were planned a week in advance.

Rummel notes Oziel was reporting on something Erik Menendez said. Rummel says Oziel was “completely discredited at trial” and asks Garland to ask Lyle about the nature of his discussions with Oziel.

“We are now talking about what Dr. Oziel recorded that a different person said to him,” Rummel says.

Garland says she doesn’t want to have a discussion that may or may not prove or disprove the validity of the defense or the jury’s findings.

“I don’t want to invite your client to testify about something that could be an issue in a later court proceedings,” Garland says.

Rummel challenges there is an inherent unfairness in basing questions on Oziel’s testimony, which she says is inaccurate.

Garland disagrees with Rummell’s assessments of her ability to rely on appellate documents.

DDA Milius says Lyle opened the door to this by writing about this topic to show his “insight” into the crime.

“If we don’t have this questioning both by the prosecutor and the commission it goes unchallenged, and I don’t think that is the appropriate forum … there is a reason we have more than Lyle Menendez in this hearing,” Milius says.

Rummel again says her objection is to “pitting Lyle’s insight against one appellate decision from a second trial without real consideration of who testified, what they testified to” and issues regarding the exclusion of sexual abuse evidence from the second trial.

Garland again says trial evidence is not relevant to the hearing because they’re not retrying the case or making “evidentiary decisions here.”

They move back to Q-and-A with Lyle.

“I realize now there were no guns. But at the time I had those beliefs. I no longer believe that they were going to kill us, in that, moment, today. At the time, I had that honest belief.”

“Really the only thought in my head was it was happening now, I needed to get to the door first. Fear overwhelmed reason. I don’t have a great explanation for why I felt such terror in those moments,” Lyle says.

Garland asks Lyle about his feelings and emotions post-murder.

“Ummm … I dropped my gun and walked out. I think shock. Numb at that point. Still panicked for a while. At some point I realized I should be expecting the police … kind of just collapsing into this feeling of the same emotion that put me in the room I was still in.”

Garland asks if there was any kind of relief, happiness, satisfaction. Lyle says no.

Garland asks if he ever had feelings of relief. “I had feelings of regret, shock,” Lyle says.

Lyle said there was a “total, sort of crumbling of my life” and even some resentment toward Erik in the weeks after the killings.

“I felt this shameful period of those six months of having to lie to relatives who were grieving just very much affected me. I felt the need to suffer. That it was no relief … I sort of started to feel like I had not rescued my brother. I destroyed his life. I’d rescued nobody.”

Garland questioning if Lyle’s actions post-murder are consistent with the emotions he described.

“I think they’re not consistent with it. I think they’re both true. I didn’t want to reveal to my Aunt Terry and to my family why this had happened and who my parents were behind closed doors. I also didn’t want to go to prison, which I kind of equated with being separated from my brother.”

Rummel asks Garland to be specific about what she means by “actions.” Garland points out the spending spree Lyle and Erik went on post-murders – buying cars, fancy clothes, a restaurant, etc.

Garland asks if spending/having “flashy things” helped him cope with his sorrow.

Lyle says it helped him feel good in the moment, lifted him out of “this anguish … my life had just collapsed without my parents.”

Garland asks how much money Lyle thinks he spent. He begins describing purchases but doesn’t give a dollar amount. Rummel redirects him to this point and Lyle says, when you include a $60K vehicle, maybe $100,000 was spent. Lyle says “the restaurant” was a business purchase for his uncle.

Garland asks why Lyle bought a Porsche.

There’s a pause in the hearing as DDA Millius has dropped off the call. He quickly returns.

Garland asks if one death gave Lyle more sorrow than the other.

“My mother. Cause I loved her and couldn’t imagine harming her in any way and I think also I learned a lot after about her life, her childhood, reflecting on how much fear maybe she felt,” he said. “I learned from her psychology, her therapist, that she felt shame.”

“I had a deep connection with my father. He was the one who sort of guided my life … he had his plan. I was in his plan. I just felt lost without him. I had the opposite of relief, I had zero relief,” Lyle says.

Garland asks about how Lyle described the crime as impulsive with the “sophistication of the web of lies and manipulation you demonstrated afterwards.” She says she’s referring to scripts given to witnesses, the attempts to destroy a competing will, “escape plans from jail.”

Lyle again says there was no plan it was “a lot of flailing in what was happening but I had more time to think about it sitting in a county jail alone in a cell all day.”

Garland again focused on Lyle coming up with “sophisticated stories” to have people lie for him.

“I hoped that they would help, so to some degree, I trusted them.”

Garland asks if Lyle thinks he’s a good liar. He says no, not now or then.

“Even though you fooled your entire family about you being the murderer, and you recruited all these people to help you … you don’t think that’s being a good liar?” Garland asks.

Lyle says the remorse he demonstrated gave people a “strong belief” that he didn’t have anything to do with it.

Garland said she is done with her questions about the crime itself.

Commissioner Patrick Reardon takes over questioning on “post conviction factors,” meaning his prison behavior.

Lyle confirms he came to Donovan (the prison where he’s currently housed in San Diego) in 2018. Says he wants to focus on that time period until now.

Reardon asks Lyle if Oct. 24, 2024 is the closest he came to believing he could be freed. Lyle says yes. (This is the date that former L.A. Dist. Atty. George Gascon submitted the petition to resentence the Menendez brothers.)

Reardon says in reviewing Lyle’s file, it felt like he was reading about “two different incarcerated people.”

“You seem to be different things at different times,” Reardon says. “I don’t think what I see is that you used a cell phone from time to time, there seems to be a mechanism in place that you always had a cell phone.”

Reardon says Lyle had access to a phone nearly all the time from 2018 to Nov. 2024, and Lyle doesn’t deny this.

Reardon points out Lyle has a good work history and an excellent educational history, as Lyle is currently working on his masters.

Reardon asks if the board should give serious weight to Lyle taking part in self-help programming if he was using a cell phone.

Reardon highlights and lauds Lyle for the Greenspace program and other mentorship work, noting at that time it was when there was no guarantee Lyle would ever get out of prison.

Lyle tries to rationalize cell phone use, says he was using the device to stay in touch with his family, his community … “I felt like it served that.”

Lyle didn’t see it as him separating the criminal and non-criminal parts of his life. He didn’t think he was harming anyone.

“You’re a bright guy. You have a college degree … I’d think you would understand” that use of a cell phone taints the good things Lyle is doing in prison, Reardon says.

Lyle says he sometimes gets so focused on service work that he overlooks the means.

Reardon questions if this type of behavior could get him in trouble outside of prison.

“I had convinced myself that this wasn’t a means that was harming anyone but myself in a rule violation. I didn’t think it really disrupted prison management very much,” Lyle said.

Reardon acknowledges Lyle plead guilty to two cell phone violations. Nov. 2024 and March 2025.

There’s three other cell phone allegations under which Lyle was found not guilty.

Reardon notes it’s the same one of Lyle’s cellmates who accepted responsibility in all of those cases. Reardon questions how that happened (seeming to imply the other inmate took a disciplinary hit for Lyle.)

All these cell phone incidents were at a time when Lyle lived in a dorm with six people (including himself). Often someone would take responsibility for the phone who didn’t have anything to lose (i.e.: wasn’t bothered by losing family visit privileges).

Lyle acknowledges conspiring to use the phones was “gang-like activity.”

Lyle says he and his cellmates probably went through at least five cell phones.

Reardon asks if Lyle remembers what personality disorder he was diagnosed with, which Lyle says had to do with having “anti-social, narcissistic traits.”

Lyle again repeats he sometimes justifies rule breaking if it furthers a positive goal.

“I would never call myself a model incarcerated person. I would say that I’m a good person, that I spent my time helping people. That I’m very open and accepting,” says Lyle, adding that he does a lot of good work with the vulnerable and picked on populations in prison.

“I’m the guy that officers will come to to resolve conflicts,” Lyle says, calling himself a “peacekeeper.”

“At the time I didn’t feel that using the phone was inconsistent with that.”

Lyle says the first time he was caught with a phone, he allowed the CDCR investigators to unlock it to prove he wasn’t involved in criminal activity, and Lyle internalized that as it being less of a problem that he wasn’t using it for criminal activity.

Reardon asks how Lyle knows none of his cellmates are using a phone for criminal activity if they share a phone. Lyle says that’s a good point, he doesn’t know.

Reardon raises how cell phones can be used to order hits, move drugs in the prison, or coordinate attacks on officers.

Lyle acknowledges he became more cognizant of the problems these things can cause as time went on.

Reardon notes its a positive that Lyle immediately took steps to address his issues with cell phones, including establishing a support network.

Reardon asks why Lyle needed the illegal cell phones to make calls to family if he had a tablet for legitimate call use. Rummel challenges that this needs to be discussed confidentially.

Rummel says this will involve the public notoriety of his case and conduct by CDCR staff, as to what his thinking was on why the tablet was insufficient.

There is a recess to discuss Rummel’s request at 12:21 p.m.

There will be a 15-minute break.

5. 2:34 pm – 8.22.25

Garland says they will keep the session public.

Rummel says they will only discuss one of the issues then.

Reardon asks again about Lyle using the cell phones when he had a tablet.

Lyle again references privacy. He says many of his communications were being sold to tabloids.

Rummel says staff who were monitoring Lyle’s communications on the tablet were selling details of Lyle’s communications with his wife and family to tabloids and other media. Lyle confirms this.

“I felt like the phone was a way to protect … privacy,” Lyle says.

Reardon asks why Lyle didn’t just send written communications to Lyle. Lyle agrees this would have been better. Rummel points out that CDCR staff monitor snail mail as well.

1:10 p.m. – Garland resumes questioning. She has follow-ups on the cell phones.

She asks if he was trying to hide or turn off the cell phone when officers approached him. Lyle says he was on a video chat and the officer was there. I did take the steps to disconnect from the video chat, “I might have even said goodbye.”

Garland says the record is more “deceitful,” than Lyle’s description in the hearing. He again says he “disconnected the call, I did turn it off, and I handed it to him.”

Lyle says Donovan was the first place he got access to a cell phone in the prison system.

Lyle says there was “a lot of stress in his marriage” at the time he began using phones in Donvoan, and he thought the phones and more conversation would help with that.

Garland notes as a result of March 2024 phone violations, Lyle lost his family visits as a result oh phone use.

Lyle calls that a wake up call, but Garland notes he “did it again” and cuts him off. He is now barred from family visits for three years.

Garland asks Lyle about manipulating people inside with his Men’s Advisory Council position.

Lyle said this gave him access to wall phones more often, and he was attacked over it. Lyle says this sometimes led to bartering and favors. This was because Lyle had control or some control of the phone list, as to who would get to make calls and how long, and Lyle says he manipulated this to his benefit.

Garland asks for more examples of using the position to manipulate other inmates or leverage it to his advantage.

Lyle talks about getting to know CDCR staff as human beings over time and became more cognizant of how cell phone use in the prisons impacts them.

Garland asks if Lyle thinks he’s treated differently due to his celebrity status or his position on Men’s Advisory Council.

Lyle says in some ways he thinks he was scrutinized and searched more.

Garland notes the risk assessment found Lyle would face a “moderate risk” of violence if released. She asks Lyle’s thoughts.

Garland reads from risk assessment, says doctor found Lyle has anti-social traits, entitlement, deception, manipulation, not accepting consequence.

Lyle says he’s talked through these things with his doctor, “those elements were there with the cell phone use, I recognize them.”

Garland asks if Lyle engaged in deception around the time of the crime.

Lyle says he used deception to survive his childhood, says his family’s home life was governed by the concept of “lie, cheat, steal, but win.”

He doesn’t agree with the idea that he has “narcissistic traits.”

“They’re not the type of people like me self-referring to mental health … or who go to a doctor and say hey can we help understand my personality better, or work on themselves.”

He says Jose was a narcissist with 0 self reflection or zero concern with morality and “I just felt like that wasn’t me.”

Garland asks about Lyle writing about benefits of being housed separate from Erik even though they also campaigned to be housed together.

Lyle talks about the positive of being separated – it helped him figure out himself, to learn his identity other than “big brother” – but also says they wanted to be able to be together given the strain on the family to not visit them both at the same time, and because they shared trauma and a bond throughout their incarceration.

Garland asks about status of Lyle’s marriage. He says they’ve been having problems for 10 years, in part due to the weight of them both coming from an abusive background.

Garland reads from the risk assessment however that Lyle and his wife thought about or heavily considered changing their marital status due to his possible release. Lyle says their status changed quite a few years before resentencing. Lyle is currently romantically corresponding with three different women, according to Garland, but Lyle says he’s closest with his wife, his biggest supporter.

Garland says Lyle has had hours of visits with a woman in the UK, increased since Lyle’s visits from his wife slowed. Lyle says this was previously romantic but it has since been ended.

Garland notes Dr. Hart found Lyle is a “very low” risk for violence upon release, as compared to risk assessment finding that he was a “moderate” risk.

1:49 p.m. – Clarifying Questions begin

DDA Milius is up first. Garland asks to restrict questions to 15 minutes.

Milius asks if Lyle thinks its important to tell the truth or have the truth be told in judicial or disciplinary or other hearings. Lyle concurs that it is.

Milius asks about Lyle’s suspension from Princeton, that it was concerning plagiarism, which Lyle again confirms.

Millius asks Lyle to confirm he conspired to get three witnesses to lie at trial. Lyle says yes.

Millius asks about Tracy Baker lying on the stand about his mother’s attempts to poison the family, the script referred to yesterday. Lyle says that he asked Tracy to lie that she was there, but does not address whether his mother actually attempted to poison the family at a dinner.

Milius asks about Lyle’s reaction to being disinherited. Lyle says it “didn’t have any effect on me.”

Rummel begins questions.

She asks about queues Lyle knew they were in danger the week of the killings.

Lyle said his father’s silence was concerning after Erik reported the abuse to Lyle. Remembers Jose saying “what does it matter anymore?” when Lyle asked about a tennis camp.

Lyle remembers Kitty shouting “no one ever helped her” when they confronted her about failing to stop Jose’s abuse of Erik.

Lyle’s face turns red and he doubles over briefly, sniffling, tears visible.

“I couldn’t wrap my mind around the fact that she knew” about the abuse, Lyle said, still struggling to speak.

Rummel asks why Lyle struggles to discuss his mother’s sexual abuse of him.

“There’s so little love in my relationship with my Mother that was overt, we’d sometimes have these moments of connection … I get that it’s abuse, but there was a lot of love in it. I know when I talk about it someone else is going to use it as an abusive event, and I don’t like it.”

He says he didn’t want it to come out at trial.

Lyle long believed none of his relatives knew “the dark side of what is happening in this family” and he felt obliged to help keep Jose’s secrets.

Rummel asks if Lyle’s sense of entitlement is borne out of Jose’s habit of being a “fixer” in Jose’s life. Lyle seems to concur but mostly just repeats Rummel’s language. “I hid behind my Dad.”

Rummel guides Lyle to push back on the narcissism diagnoses, as he notes he feels he’s very empathetic, pointing to his work with with inmates convicted of sex abuse, which have helped him forgive his father.

“Groups live in the shadows at CDCR, they get bullied and mocked. I’ve been there. I’ve experienced it.”

Lyle says he tries to communicate that they’re “all the same,” meaning equals.

“My life has been defined by extreme violence. I wanted to be defined by something else,” Lyle says in tears.

Non violence was a promise he made to his grandmother, and says this has played a big part in his behavior inside CDCR.

Rummel asks how the resentencing petition filing flipped a switch or changed things for Lyle.

“It took a few months. It took my brother and I really wrapping our mind around it because you’ve sort of lived this moment for too long. Eventually I wrapped my mind around it.”

Closing Arguments Being At 2:33 p.m.

6. 3:45 pm – 8.22.25

Closing Arguments:

Millius questions if Lyle has “genuinely” taken accountability for his conduct. He cites Lyle’s inability to “follow basic rules while in a highly structured setting.”

Millius tallies eight violations for which he’s found guilty. Says Lyle’s continued willingness to commit crimes and violate prison rules shows a lack of growth.

Millius says the recency of the cell phone violations is concerning, and indicative of a broader “pattern of conduct that culminated in 2024.”

He says the lack of violence doesn’t mean Lyle doesn’t pose a danger if freed. Millius again highlights the contradiction of Lyle engaging in rules violations while leading the Men’s Advisory Council. Says it shows Lyle “struggles with honesty.”

Says Lyle decided “based on his own personal analysis, [that] the rules don’t apply to him.”

“There is no growth. It is just who Lyle appears to be,” Milius says of Lyle, with respect to lying.

“When you look at him, Lyle has a long documented history of lies made to avoid the consequences of his own actions.”

Milius goes through all the brothers’ attempts to cover-up the murders again.

“This is exactly consistent with his current behavior. When he commits a violation, he lies about it, and tries to avoid responsibility.”

“Today, Lyle continues to lie about the central issue in his parents murders,” Milius says, still giving no weight to the idea that the brothers had any legitimate fear their parents would kill them.

Milius raises how the brothers bought the guns, that it was out of town to distance themselves from the pre-planned killings.

Rummel Closing:

“We are 36 years and a couple days from the date of this crime. More than a lifetime. Lyle Menendez spent the first 21 years of life in the prison of his home, and the rest of his life in prison.”

Rummel says Milius’ revisiting of how Lyle tried to cover up the crime 35 years ago is irrelevant, as the legal standard for parole has to do with the danger Lyle poses now, not then.

Says the D.A. “clings to their 1990s theory of the case” and ignores the role the abuse played in the shootings.

“I hope that we’re in a place today that we have a deeper understanding of childhood sexual abuse.”

Rummel expresses frustration that the hearing has spent almost no time focused on Lyle building positive relationships with CDCR staff, with his laudable work starting programs.

“How many people with an LWOP sentence come in front of this board with zero violence, despite getting attacked, getting bullied, and choose to do something different,” she says, adding Lyle has never touched drugs or alcohol inside.

“We spent no time at all talking about the hundreds, if not thousands, of hours, Lyle spent following rules in prison,” she says, exasperated by the focus on cell phone use.

“This crime arose from trauma, from unresolved trauma, from fear, from sadistic abuse, and from cruelty. Mr. Milius wants this to be some sort of pre-planned crime,” she says.

Rummel questions how finance could have been a motive if the brothers knew they were out of the will for a year before the killings.

She asks if they had a master plan to kill their parents why did they use very loud shotguns in a quiet Beverly Hills community.

Rummel notes the only acts of violence Lyle has ever committed were the murders themselves.

“This board is going to say you’re dangerous because you used cell phones … but there is zero evidence that he used it for criminality, that he used it for violence. He didn’t even lie about it.”

Rummel argues Lyle has been extremely candid today.

“He has reconstructed the prison yard. He has created groups on adverse childhood experiences.”

“The family, who you will hear from … who know him, know him better than any of us can hope to know him …

“Every psychologist who has examined or discussed abuse with Mr. Menendez … believes the abuse and believes that this crime was driven by trauma. And all of them believe that he does not pose an unreasonable risk.”

“This family knows Lyle Menendez. They’ve known him as a child. They saw what was happening in that house. No one excuses what he did … but they all understand it.”

Lyle Menendez Closing Statement:

(Lyle’s face is reddened and he’s crying, his voice strained the entire time.)

References Aug. 20th as the anniversary of his crime.

“It’s the anniversary of a crushing day for so many in my family … I think about all the phone calls on that day with the shattering news and the loss and the grief.”

“Despite all of this they are still here, showing up for me, disrupting their lives, dealing with public scrutiny … and I will never deserve it.”

Says he takes “responsibility for all this pain. My Mom and Dad did not have to die that day.”

Says his decision to use violence that day was solely his, it’s not his “baby brother’s” responsibility.

“I’m profoundly sorry for who I was … for the harm that everyone has endured.”

Talks about his grandmother teaching him to make pinky promises, and they made one in county jail, it’s a moment he’s thought about 1,000 times.

“I will never be able to make up for the harm and grief I caused everyone in my family. I am so sorry to everyone, and I will be forever sorry.”

Family Statements:

Maya Emig, attorney:

Refers to Thursday’s hearing as very difficult “It was difficult in the decision. It was difficult with respect to asserting rights.”

“There were 55,000 pages that were submitted to the board …

Highly emotional, expresses extreme frustration with the D.A.’s office clinging to the “old narrative.”

“What are you afraid of? Which parole condition is Mr. Menendez going to violate? He’s got a wonderful support network,” she says, noting again that Lyle has no allegations of violence his entire time inside.

“There is no legitimate purpose in further incarceration.”

Break at 3:36 p.m.

7. 4:53 pm – 8.22.25

Anamaria Baralt:

“Lyle has not been a violent person in his entire life. He is not a violent person today. In 54 years I have not heard Lyle raise his voice, not once.”

She tells a story of Jose’s perfectionism, where she saw Jose tie Erik’s legs together while he was in a pool to correct an error in his breast stroke for competitive swimming. She claims Erik almost drowned as she and Lyle watched on in horror.

“I believe, that they believe, that nobody was going to protect them,” she says of the brothers.

“I’ve heard so many times over the last 35 years, why didn’t they just leave? And thankfully the criminal justice system has started to catch up with the brain science that trauma and childhood abuse create the illusion that there” would have been no escape for Erik and Lyle, she says.

“There is a difference between having guards listen and read your messages. That is not the same as having your thoughts, my thoughts, his wife’s thoughts, sold to media and broadcast,” she says, invoking Lyle’s explanation for cell phone use.

She said the family, now understanding the severity of cell phone violations, have all signed up for Global Tel Link so they can call on approved phones.

“I believe my father would be very proud of the man [Lyle] is today.”

She again invokes how some of the oldest relatives are close to death and today’s hearing is their only shot to see Lyle again beyond prison walls.

“I am begging you, commissioners … make this torture end. This 36 year nightmare. Let us put it behind us.”

#

Stuart Hart:

Former Indiana, ret. Indiana State University professor

“He’s been punished, brutally, by life. And yet … he’s not a threat to anyone.”

Questions “who among us could do as well” as Lyle, given the circumstances of his life.

Father Ken Deasy:

Said he doesn’t condone murder, but he does oppose bullies.

He refers to the judicial system and prison system as “bullies.”

“When you say to Lyle that he’s had to campaign that he was the most loved … he just was campaigning seeing some sense of growth and you don’t see that in prison. You don’t see that sense of growth.”

“What does it mean to be a risk to society?”

Marta Cano Hallowell (speaking for Marta Menendez Cano, her mother):

“She loved her brother deeply, as well as she loved her sister-in-law, Kitty and her nephews.”

“Mom quickly put aside her grief and took on a supportive role for both Lyle and his brother Erik, understanding the fragility and complex emotions of teenage boys.”

Says her mother has kept very close contact with Lyle, speaking with him 2-3 weeks, visited 2-3x per year, and did this for 35 years.

“I just hope that Lyle, and his brother Erik, get released from prison before I die.”

Eileen Cano (Jose & Kitty’s niece, she appears to be reading the verbatim same letter she read yesterday)

Says she used to look up to Jose as a mentor.

“You can’t imagine how devastated I am today to find out there was a second side to them.”

Describes Lyle as a kid, how fun he was, and “protective of his younger brother Erik to a fault.”

“I wish so much that I had known and I could have done something to protect Lyle and his younger cousin.”

Talks about learning of her aunt and uncle’s death by a breaking news alert on TV.

“Never in a million years did I think Lyle would be capable of doing such a horrible thing.”

Says she avoided watching any of the trials.

Says she’s speaking for three family members who couldn’t be there today: Jose’s mother, who she guarantees if she were alive today would be “pleading” with the Commissioners to release Lyle.

She says she knows Lyle lives “every day with true remorse.”

“I am amazed by how much he achieved, despite facing life without parole. While most people surrender to the crushing weight of prison life, Lyle rose above it.”

“Lyle will not be a risk to the community because we as a family will hold him accountable.”

“Delaying his release would serve no purpose. Lyle is not the man who went to prison 35 years ago.”

Tiffani Lucero Pastor:

“We are here supporting these men because they are reformed.”

“I really hope the state of California understands the complexity of where we sit … I hope the state of California understands how awful this is for us.”

“The man before you today, Lyle, shows his love in deeds, not just in words.”

“I ask that you take what our victim family has said to heart. We forgive Lyle. I forgive Lyle. I forgive him for killing our aunt and uncle. I forgive him for trying to cover it up … we want this to end. You have the power to end our individual and collective suffering.”

Break

8. 5:33 pm – 8.22.25

Tiffani Lucero Pastor: (speaking on behalf of Joan Vandermolen):

“The day Kitty died devastated Joan beyond belief.”

“Joan describes that what she has witnessed in Lyle over the last three decades as nothing short of stellar … she is so proud of the work he has done to support others who are in need of support.”

Marta Cano Hallowell (Jose’s niece & goddaughter):

“Lyle had truly changed. He was no longer the spoiled, seemingly cocky and arrogant kid with whom I had spent many summers. He had become a caring, introspective and empathetic adult,” she says of her interactions with Lyle in prison years after the murders. She adds she was especially impressed with his progress at a time when he had no hope of release.

They now speak regularly, despite that being rare and difficult in the wake of the murders.

Tamara Goodell-Lucero (Kitty’s great niece):

She talks extensively about the confusion and shame Erik and Lyle must have felt as sexual assault victims at the hands of their parents. She’s in tears the entire time.

“He has dedicated himself to a career for making conditions for incarcerated individuals in the California correctional system better.”

“Lyle has intentionally worked to build a life in prison that abhors violence and avoids criminal thinking.”

She tells a story about Lyle playing flag football on a yard and taking repeated violent shots in the game from inmates who targeted him because of his last name.

Says Lyle told her he would “take back every second” of what he did on the night of his parents murders.

Rummel interrupts to claim the audio of Thursday’s entire hearing is public. She repeats her objection to media presence in the hearing and implies media access to the hearing has led to this “leak.”

There is now a break due to this.

CDCR spokesperson in the room where I am (at CDCR HQ, not in the hearing or where anyone in the hearing can hear it) says the audio was accidentally shared. Anyone submitting a public records request for that audio will get it “very soon,” per spokesman.

9. 6:00 pm – 8.22.25

Garland confirms the audio of Thursday’s hearing has been released. The plan was to release it, pursuant to public records act requests, she says.

Rummel says she’s asked for audio of a parole hearing in the past, and it has never been released.

“It’s highly unusual. It’s another attempt to make this a public spectacle,” she says.

She says this is impacting their Marsy’s Law rights (that’s Californai’s victims bill of rights) in this hearing. Rummel requests to adjourn the hearing as this is now no longer a fair hearing in her mind.

“CDCR is not following its own rules. We are sitting here asking Mr. Menendez to follow rules … and in the middle of this hearing, we find out CDCR is not following its own rules. It’s outrageous.”

Garland says the panel has not heard any audio and spent an awful lot of time on this hearing. She says she doesn’t understand how the audio impacts this hearing.

Rummel says none of the family members knew their voices would be put out into the public.

“IF CDCR is going to release the audio of this hearing, we would like a decision before we proceed.” – Rummel says.

Attorney Maya Emig asks for the exclusion of her own statement now –

“You do not have the permission to do this, period.” Does not want her audio out in the public domain.

“There has to be notice given. It’s unacceptable. Those statements were put into the confidential record for a reason,” Emig says. (I am unclear what she means by this, transcripts of parole hearings are public record.)

DDA Millius says he does not see how the release of audio impacts the hearing. Millius says the leaked clip only has to do with the Commissioner’s ruling at the end of the hearing. He notes that at some point a transcript will be released. (There is a clip on ABC for those of you looking.)

Rummel requests a break to confer with Erik. And is again asking to confirm that CDCR had always planned to release the audio and had not informed the victims family. Rummel demands to know if they plan to release audio of today’s hearing before proceeding.

“What policy allows for this to happen in this hearing but literally no other hearing?” she asks. “It’s never been done. My suspicion is that CDCR should have embargoed this, and they failed to … and it’s ironic to me that we are sitting here for hours talking about Mr. Menendez following CDCR policy, and they are not following their own policy,” Rummel says.

They go on another break

10. 6:31 pm – 8.22.25

Garland confirms there has been a policy based on an interpretation of the public records act that if someone requests an audio recording of hearings, they may receive them.

She doesn’t know how long that has been going on. She points out that the transcript of this hearing would be released at some point regardless, as CDCR regulations allow the release of a board hearing transcript within 30 days. The board proposes they will hold off on releasing the audio until the parties have a chance to file objections to their statements being made public.

“I don’t think you can possibly understand the emotion of what this family is experiencing. They have spent so much time” trying to protect their privacy and dignity, Rummel says.

Rummel says no one warned the victims that “your voices, speaking your most intimate private thoughts … are going to be released to ABC in the middle of the next hearing while you’re trying to make statements to your loved ones,” Rummel says.

“We came into these hearings hoping and expecting a fair and impartial hearing where Mr. Menendez could be heard, be considered and be understood. And we have a public spectacle and this has exacerbated it twenty-fold. And we now have family members who are not going to speak,” Rummel said.

Rummel said she plans to seek to seal the transcript from this hearing under Marsy’s Law.

Rummel says she believes yesterday’s hearing was also fundamentally unfair.

The remaining victims’ statements will not happen, per Rummel, due to the audio leak as the victims do not want to speak.

“Unless we can be assured that the audio of today is not disclosed until a court can hear that it should” or should not be disclosed, she said.

Points out CDCR never turns around

“We don’t even get a transcript in 30 days, and y’all are blasting audio out across the news waves?” Rummel asks.

“We’re not confident in the board’s ability to protect the victims at this point,” Rummel says.

DDA Milius believes the hearing should continue, he says he’s yet to hear any particular violation of the law. He notes the print transcript would have always been public. He repeats that the commissioners’ have not listened to the audio.

“Mr. Milius does not want to protect the victims in this case. That’s been a pattern of his office,” said Rummel, who is clearly very angry.

Tiffani Lucero-Pastor (victims relative) now yelling at the commissioners and begins reading from Marsy’s Law.

“I want to know why the state of California and this prison system has wholly dismissed our rights as victims. Who has decided our rights as victims get thrown out the window?” she asks. “This is disgusting. This process is damaged and broken.”

Screams that Milius should be “ashamed of himself.”

“I am tired of living my life in the shadows because of this bologna. I have protected myself, I have stayed out of this, I have not had a relationship with two human beings because I was afraid and I came here today and I came here yesterday and I trusted that this would only be released in a transcript … a transcript is far different from an audio recording,” she says.

“You’ve misled the family, and now to compound matters, you’ve violated this family and their rights,” she says.

Commissioners take another break to speak at 6:42 p.m.

11. 7:21 pm – 8.22.25

Garland confirms the audio will not be released from today’s hearing until Rummel has the opportunity to file an objection or something in court to contest their release.

Rummel – “It’s my impression from the family members that that’s not enough of an assurance” to allow for the victims to finish speaking today

We are now resuming victim statements.

Teresita Baralt:

“I want my nephew to hear how much I love him, and believe in him. I’m very proud of him and I want him to come home,” she says in tears, adding she is not comfortable reading her pre-written statement into the public record given the audio situation.

Rummel says a number of victims will refuse to speak now, out of concern their audio would be leaked.

Karen Mae Vanermolen-Copley and Erik Vandermolen say they are uncomfortable speaking.

Break for deliberations and decision at 7:16 p.m.

12. 8:07 pm – 8.22.25

All information is now reportable.

The board returns at 7:42 p.m.

Garland thanks the room for their patience — “This has been an incredibly challenging day, in so many ways, in different ways for different people.”

“The panel has found today that there are still signs” that Erik poses a risk to the public. It is a minimum denial length of three years.

“Ultimately there are issues that I am going to address that I hope will provide some guidance” for your next hearing.

They begin giving the decision without Erik in the room.

Garland says Erik’s crime lacked self-control, was impulsive and made very poor decisions during the commission of the crime. She says he had “poor threat perception” with regard to the risk Jose posed. She specifically cited shooting Kitty one final time as extremely “callous.”

Garland also highlights Erik’s role in the cover-up — lying to police and working to avoid prosecution.

Garland says Erik has a strong support network and good plans for his post-release life and is “setup for success” when he walks out the door. She also commends Erik’s lack of violence in his prison record, his work on programs inside and his positive relationships with other inmates and staff.

“We find your remorse is genuine. In many ways, you look like you’ve been a model inmate. You have been a model inmate in many ways who has demonstrated the potential for change. But despite all those outward positives, we see … you still struggle with anti-social personality traits like deception, minimization and rule breaking that lie beneath that positive surface.”

She says “incarcerated people who break rules” are more likely to break rules in society.

“We do understand that you had very little hope of being released for years.”

“Citizens are expected to follow the rules whether or not there is some incentive to do so,” she said.

Garland says they did give “great weight” to the youth offender factors, since Lyle was under the age of 26 and very susceptible to his “negative and dysfunctional” environment created by Jose.

Garland said she blanched at Lyle answering “no” to the “are you a good liar” question.

Ultimately, she said, Lyle needs to be the person he shows he is in running programs for other inmates.

“Don’t ever not have hope … this denial is not … it’s not the end. It’s a way for you to spend some time to demonstrate, to practice what you preach about who you are, who you want to be,” Garland says. “Don’t be somebody different behind closed doors.”

She says he’ll be considered for an administrative review within one year, and Lyle could be moved up to a hearing as soon as 18 months.

Hearing adjourned at 8:07 p.m.

COMPLETE OFFICIAL TRANSCRIPT:

LYLEMenendez, K13758, 2025-08-22 corrected_1