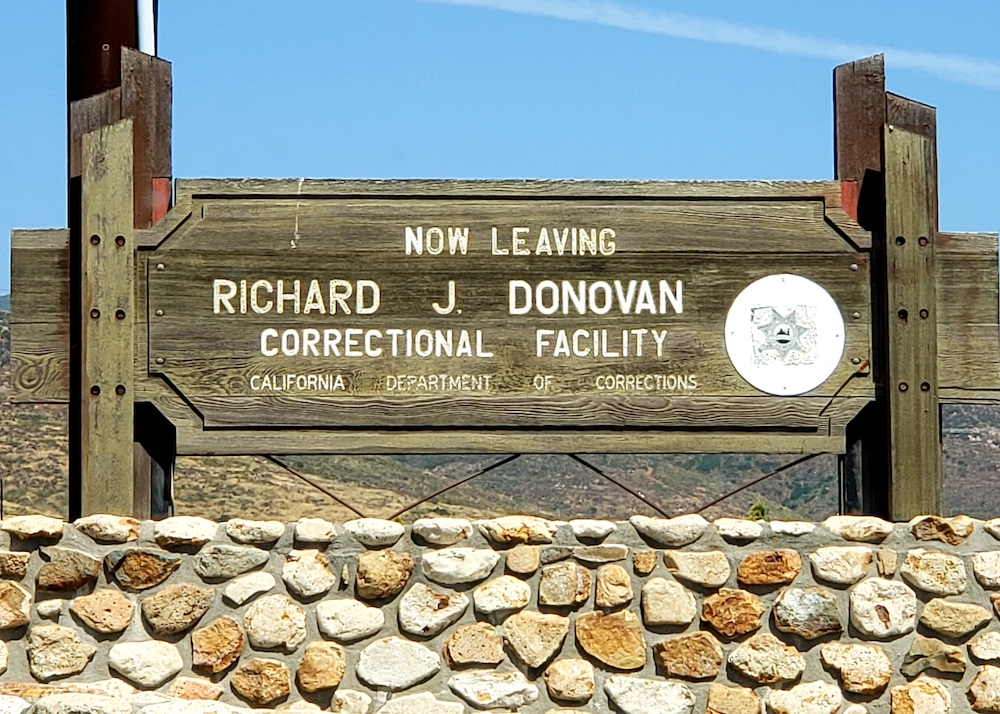

The 780 acres of California’s Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility are about a half hour east and slightly south of downtown San Diego.

The 780 acres of California’s Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility are about a half hour east and slightly south of downtown San Diego.

The penitentiary tops a mesa near an industrial park, just over a mile from the Otay Mesa border crossing.

I always know when I’m close to the jail because my cell phone buzzes with a text message:

Welcome to Mexico.

Lyle and Erik Menendez are both inmates here now, 22 years after being forbidden from seeing or talking to each other.

The current prison population is just under 5000 — in a facility designed to hold 2200. Small cells that were originally built for one now hold two. There are large dorm areas housing many of the inmates.

Lyle and Erik sleep in separate small dorm rooms; each hold six inmates. Lyle’s cell has two bunk beds. He has one of the two individual beds in a corner.

The prison day begins with breakfast at 6:30 am. Lyle prefers to sleep in a little later. He makes his own food throughout the day with ingredients from packages that can be mailed to him. The brothers are both Group A prisoners and have earned special privileges.

Prisoners are allowed recreation and exercise in the morning. Inmates with jobs go to work. Lunch is a sandwich and fruit in a brown bag that can be eaten at any time. Inmates can go outside in the individual prison yards during the afternoon.

At 4 pm, there is a formal count of all inmates; they are required to stand in place.

I’ve had to end calls with Lyle for the count. Other conversations have been unexpectedly interrupted by yard calls or lockdowns — when guards investigate an incident and inmates must immediately lie on the ground. I’ve heard shouting and other loud noise when Lyle has had to suddenly drop the phone.

After dinner, some prisoners are allowed outside again.

At 9 pm, everybody is back in their cells. The doors are locked until six the next morning.

The CDCR recently made visiting much easier at Donovan. I visited Lyle last month.

You can now drive right to Lyle’s building. Previously you had to make appointments online, park far away, ride a small bus to a processing building and then take another bus to the brothers’ visiting room in E Block.

The only things you are allowed to take inside are a drivers license, car keys and $50 in cash — just $5s and $1s. No cell phones are permitted. You have to be on the brothers’ visiting list. Getting approval to visit takes about six weeks. After showing an ID, you are handed a light green paper pass with a smiling mug shot of Lyle.

After passing through a metal detector, you walk outside and a heavy metal gate slowly rolls open. You are temporarily inside a 12-foot high chain-link fenced cage with razor wire surrounding the perimeter until a gate on the other side opens. Locked in that cage, you feel like a character in an old 1930s prison movie.

(My first time there, I was startled; after a half dozen visits, it has become routine.)

You walk a hundred yards into a drab, gray concrete building where you hand your pass to a guard who buzzes you into the large rectangular visitors’ room.

It takes a few minutes until Lyle comes down from his dorm. A sign says the capacity is 422, but I’ve never seen that many people in the room.

There are long rows of about 60 individual tables each surrounded by four hard plastic chairs. The tables are only knee high so the guards can watch everything that’s going on. On most visits, Lyle appears within a few minutes, always smiling as we hug. Several uniformed guards sit behind a desk on a raised platform. Lyle has to sit facing the guards. In the ceiling, a dozen security cameras scan the room.

The atmosphere in the visiting room is noisy but low key.

The prisoners wear dark blue pants and light blue shirts with the yellow block letters CDCR on the back. Visitors are not allowed to wear anything blue or tan — the colors of the inmate and guard uniforms. With the $50 I carry in, I am allowed to buy food for Lyle and myself. Lyle enjoys having a meal from an outside food vendor.

The menu now includes burritos and several salads and burgers. On my most recent visit, Lyle was hungry. He ordered two salads ($10 each) and added grilled chicken (an extra $4 each). He told me this would be his lunch and dinner. I had a carne asada burrito with rice and beans ($14). The food was delicious. With the remaining $8, I bought drinks, chips, and Lyle’s favorite — an ice cream sandwich.

Many visitors can only afford the food from vending machines that line one wall. With the casual ambiance of the room and a spirited conversation, you momentarily feel as if you are just two ordinary people catching up in a restaurant — until you look to the side and see that some visitors are talking to inmates over a phone, separated by thick, heavy glass.

A sign over a small desk and chair in a corner reads “CHILDREN’S VISITING AREA.”

Next to the desk is a bookcase with several shelves of games. Large windows look out onto a cement courtyard surrounded by more tall chain link fences topped with razor wire. A dozen hard grey metal benches sit in the middle of the enclosure. Lyle and I go outside and walk laps about every 30 minutes during our five-hour visit. We pass by wives or girlfriends who are holding hands with prisoners in the corners.

Lyle is highly intelligent, and there is never a lull in our conversation. We rarely discuss his case during our face-to-face visits. He tells me how grateful he is to be reunited with Erik. They watched a movie together on a TV in his dorm room after dinner the night before our visit.

A few weeks earlier, Lyle was looking through a storage room in the prison gym and discovered a pickleball net and some pickleball rackets. Other inmates watched curiously as Erik and Lyle set up the net and played a rough version of tennis for the first time in the 29 years since their arrest.

Both brothers are fortunate to have earned their way into Echo Yard — a new program that began at Donovan and is now being rolled out to other California prisons. The San Diego Union Tribune describes Echo Yard this way:

Inside this experimental yard, classified by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as a “non-designated programming facility,” normal prison rules no longer apply. Cells are racially integrated. Sex offenders and transgender inmates are housed with everyone else. Gangs are banned. All 780 inhabitants of this yard ‘program’ are immersing themselves in courses designed to address a criminal past (anger management, victim awareness), law-abiding future (job hunting strategies, money management) and deep-seated pathologies (Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Criminals and Gang Members Anonymous). Prisoners publish a monthly newspaper, perform in musical bands, raise service dogs for wounded veterans and autistic kids. There’s Saturday morning yoga, Thursday night art class, correspondence courses in geography, history and other subjects.

Both Menendez brothers are helping others. Lyle is a passionate activist for prison reform and served as head of the inmate government for 15 years at Mule Creek. Erik created a hospice program at the jail and leads a weekly group in meditation.

Both brothers have recently started to study ASL – American Sign Language. Lyle is working on a project to have murals painted on some of the stark prison walls. Art students from San Diego State have volunteered to create the design. Lyle is hoping a small outdoor recreation area will be installed with Astroturf and some simple landscaping. The paint and supplies are being donated by Home Depot.

During one of our breaks walking laps outside, we stop and talk with one of Lyle’s friends who I’ve met before. The stocky Latino in his 40s is standing with his girlfriend. She shyly pulls out a tiny pencil and paper and asks for Lyle’s autograph.

Occasionally during our time together, other visitors sneak a glance at Lyle.

He is not the only high profile prisoner at Donovan. Sirhan Sirhan, the man convicted of assassinating Robert F. Kennedy, has been there since 2013.

Manson Family member Tex Watson used to be housed at Mule Creek prison with Lyle; now, he is at Donovan. Watson has been denied parole 17 times since his first-degree murder conviction in October 1971.

Death Row Records founder Suge Knight has been at Donovan since December 2018. The rap mogul is serving a 28-year sentence for manslaughter after running over two men in a hit and run accident which Knight claims was self-defense.

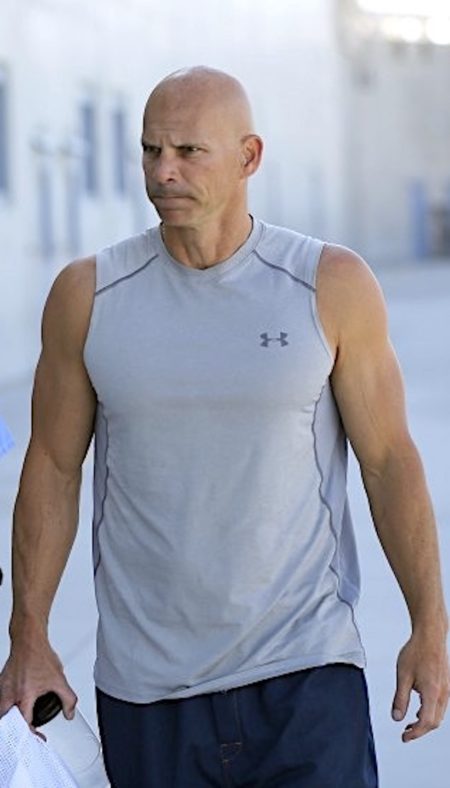

Anerae VeShaugn Brown — the rapper known as X-Raided — met Lyle and Erik several times when he was transferred to different facilities during his 26 years in the state prison system (photo).

Anerae VeShaugn Brown — the rapper known as X-Raided — met Lyle and Erik several times when he was transferred to different facilities during his 26 years in the state prison system (photo).

In March 1992, 17-year old Brown was an aspiring MC and member of Sacramento’s 24th Street Garden Block Crips. He had a deal with Black Market Records, a small indie label. Brown and three other members of his gang staged a home invasion looking for two rivals, the sons of 42-year old Patricia Harris. Harris was shot and killed. Her son were not at home.

During his lengthy trial four years later, Brown denied being the shooter who killed Harris. But the murder weapon matched the ballistics of a gun pictured on his latest album cover. The judge allowed prosecutors to play the jury an X-Raided song that included the violent lyrics, “I’m killin’ mamas, daddies and nephews/I’m killin’ sons, daughters and sparin’ you.”

Brown was convicted of first-degree murder in 1996 and sentenced to serve 31 years to life. Anerae and Erik Menendez were reunited at Donovan in November 2017. Lyle joined them five months later. Brown qualified to have his case reviewed as a youthful offender when a new California law was passed based on scientific research that says a brain is not fully developed until the age of 25. Erik was one of Brown’s supporters who wrote a heartfelt letter to the state parole board in 2015.

(The Menendez brothers who were 18 and 21 at the time of their crime are not eligible to have their case reviewed because of an exception under the law — their life without parole sentence.)

Brown was released from prison on September 14 last year. He expressed remorse for his role in Harris’ murder in a Facebook post 10 days later: “The greatest shame I feel is for the senseless death of Mrs. Harris and the knowledge that I am overwhelmingly responsible for her death,” he wrote. “It was my fault and I accept the reality that I owe a debt for her death.”

During his time in prison, the 44-year old Brown recorded more than a dozen albums – some over the phone and later ones using a small recorder.

Brown remains in touch with both of the Menendez brothers whom he considers close friends. Anerae has told me that his contact with Erik and Lyle was an integral part of his personal development to turn his life away from violence and gang banging which he now describes as “parasitic”.

Since leaving prison, Brown — who now goes by the name Anerae VeShaugn — has released a new album — The Execution of X-Raided.

Lyle flashes a warm smile when he talks about his friend the rapper.

Lyle’s upbeat attitude is a constant presence throughout all of our visits – even when the discussion turns serious.

Both Erik and Lyle have repeatedly expressed their own remorse in media interviews.

Their last appeal was turned down in 2005, but they remain hopeful that there will be a review of their case in the future.

But Lyle says the brothers have accepted that this is their life, that they will never be released from prison.

“We’ve seen too many friends get their hopes up with appeal filings and commutation requests. They’ve marked the days off on calendars,” he says.

“In the end, they are turned down and sadly sink into a deep depression.”

The brothers have spent more than half of their lives in custody since their arrest, 29 years and three months ago.

They’ve chosen to be of service to those around them, helping others who are processing the abuse and trauma they themselves experienced as children.

MORE LIKE THIS? GET THE BOOK!