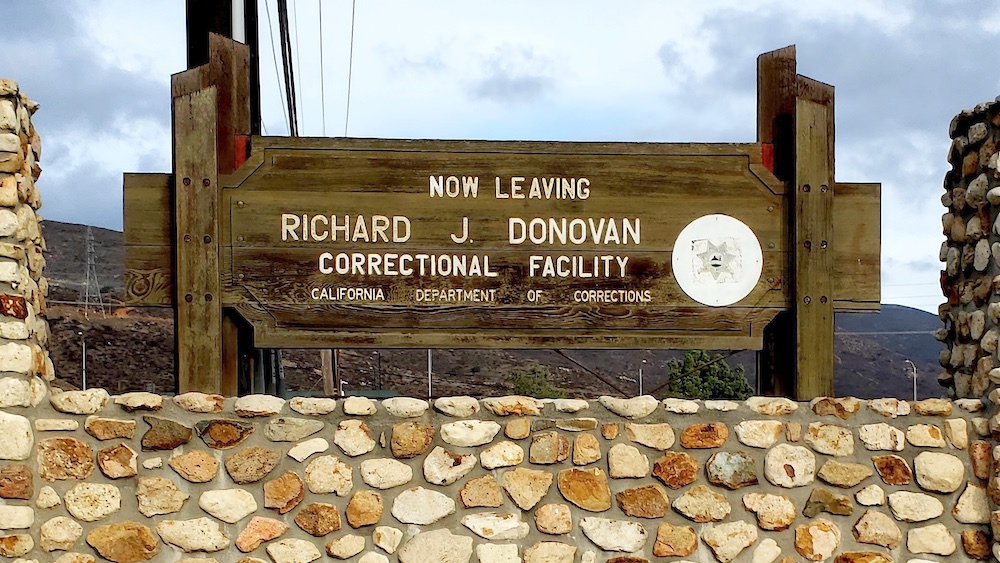

The last time I visited Lyle Menendez at the R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility near San Diego was February 23, 2020.

Within weeks, California, like the rest of the world, would be locked down because of COVID-19.

Sure, we were all unhappy to be stuck at home, but imagine trying to survive the plague while packed in prison!

The virus was not a problem at Donovan until December 2020; that’s when a shock outbreak — 700 new cases in one week — turned the sprawling lockup into a pandemic penitentiary.

Lyle and Erik, luckily, were never infected, and they are now fully vaccinated.

The California Department of Corrections COVID tracker website shows no recent active cases there.

To prepare for my first post-COVID visit two weeks ago, I had to study several pages of instructions like this:

It was not surprising that there were intricate protocols laid out on the CDCR website for coming to visit an inmate at Donovan.

The biggest change was that our leisurely five-hour visits were now reduced to a two-hour face-to-face encounter.

I drove from my home in Los Angeles to Chula Vista, the town closest to the prison. I left at 9:30 on a Thursday night and was there within two hours. Thankfully, I arrived just before closing at Tacos El Gordo, the legendary Tijuana taqueria with a branch near my usual hotel.

The next morning was unseasonably cool and cloudy.

There had been a heavy rainstorm overnight. I grabbed some fast food for the 20-minute ride out to Otay Mesa. I figured the outside caterer who provided delicious salads, burgers, and burritos in our previous visits would be gone post-COVID.

The rolling landscape near the prison was marked by an industrial park framed by nearby mountains.

It felt lonely. I didn’t see any other people on the streets as I got off the freeway, and few cars or trucks.

As I pulled up to the front security gate, an ambulance was pulling out with lights flashing and siren wailing.

It was an ominous sign: our visit could be canceled if the prison was locked down. The parking lot outside of Lyle and Erik’s home — E block — was full. Guards and staff park there — I wasn’t expecting that there would be many visitors on a Friday afternoon.

I walked into the first building at 1:40 pm — 20 minutes early.

On a normal visiting day, there would be standing room only, packed with people looking forward to spending time with loved ones. Today it was virtually empty.

There were two masked guards behind the counter — a man in his early 30s and a woman in her 20s who was probably seven or eight months pregnant, her uniform shirt barely covering her stomach. The man asked me to go back and wait in my car until it was time for my 2 pm visit.

As I sat in my car, I flashed back to the bright, sunny afternoon 32 years ago — October 1989 — when I met Lyle and Erik. This is how I described that day in my book:

After two weeks of failing to get an interview with Lyle and Erik, my editor at the Miami Herald ordered me home. From Florida, Marta Cano called her nephews on my behalf, insisting that they had to meet with me. We made another appointment for 3 pm on Friday, October 20, at the mansion at 722 North Elm Drive. This time they didn’t cancel.

The door was opened, not by either of the brothers but by Kelly, who told me she was Erik’s girlfriend. The brothers “were delayed,” she said. She was in her early 20s with blonde hair and a cheery smile. She invited me inside. We made small talk before she offered to show me around the mansion.

I felt a chill as we walked by the open double doors leading to The Room. It was empty of furniture and had a bare hardwood floor. The floor-to-ceiling bookshelves were filled and above them on a narrow ledge were dozens of tennis trophies. If I lived in the mansion, I decided I would close those doors.

After passing by a second time, I thought, if my parents had been murdered in that house, I wouldn’t even be living there.

Erik and Lyle showed up at 3:45 pm, wearing tennis whites, in sharp contrast to their dark tans. We sat down just off the kitchen in a breakfast nook, around a circular glass-topped wicker table. Within five minutes, Lyle told me the brothers were thinking of writing a book about their father’s “extraordinary life.”

Would I be interested in working with them? I agreed that Jose Menendez’s backstory was fascinating. But when I brought out a tape recorder, Lyle stopped me. “We can only meet for a short time today,” he said. “Let’s just talk and get to know each other — no tape recorders and no notes.

” Over the next hour, Lyle did 90 percent of the talking. He compared his father to John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., and described his death as a “tragic loss for the Cuban people” who “didn’t even know who he was or what he was going to do for them.”

Erik told of the books his father read, his suffering in Cuba, and that Jose was a regular contributor to Radio Martí, the Spanish-language equivalent of Radio Free Europe broadcast to the island from transmitters in Florida.

The few times Erik spoke when Lyle was in the room, he looked to his older brother as if seeking his approval. He was low-key and measured. Lyle was much more outgoing and confident, and maintained eye contact.

As I sat in my car scrolling through my phone, I was suddenly startled by automatic gunfire. Donovan has a shooting range I hadn’t noticed in previous visits — including several target dummies — so guards can practice marksmanship.

It was a stark reminder that I was visiting a high-security prison.

We swapped our masks for fresh ones provided by the prison. I received a pass — a yellow piece of paper with Lyle’s smiling mug shot and both our names. A guard wrote on the pass that I had a belt, a car key fob, a vaccination card, and $50 in cash to buy Lyle food from the vending machines. No cellphones allowed, of course, so no selfies.

Just after 2 pm we entered “the cage” — a fenced enclosure between the check-in area to the visiting building connected to E block 150 yards away.

We handed over our passes and a guard buzzed us in. There were only three of us in the large rectangular room where — before the pandemic — up to 60 inmates met with visitors.

Computer monitors were set up on tables in one corner where friends and family could have video visits. The bookcases and games were gone from the children’s area, now reduced to a mural of a farm scene leaning against a wall behind a tiny table with two benches.

We each turned over our passes to a guard behind a desk on a raised platform; he told us to sit at one of the knee-high tables.

The inmates must face the guard platform. They tape a blue paper to each table with the rules: we’re allowed a brief hug when we say hello. Kissing and holding hands, nope.

By 2:20 pm, Lyle had still not shown up. One of the women visitors queried the guard who explained the yard had been locked down because of an assault earlier in the afternoon. Aha! That explained the ambulance.

Finally, at 2:30, Lyle came walking through the door. As usual, he was smiling and looked vibrant and healthy. We hugged and stepped back to look at each other.

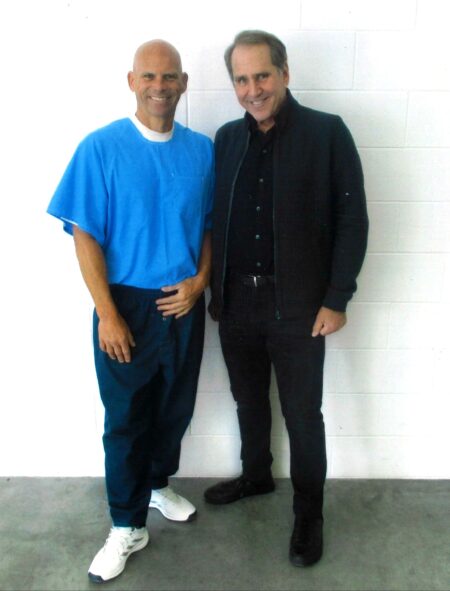

He hadn’t changed since our last in-person visit. The prisoner photo service that used to cost $1 was unavailable — another post-COVID change — so I was unable to update this photo from May 2018:

The outside food vendor was gone, so we headed for the vending machines.

Lyle asked for a tired-looking cheeseburger (which he heated up in a microwave), a Rice Krispy treat, and Diet Coke.

I had to push the buttons and insert the cash — prisoners are not allowed.

There were only two other visitors but we went outside to a small cement courtyard surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. It was cloudy but the sun was starting to peek through. We took off our masks and sat, socially-distanced, at opposite ends of a silver metal bench.

The first thing we discussed was the pandemic.

Lyle told me that the brothers were scared last December when Donovan had a major outbreak.

Fortunately, they came through that OK. They still interact and see each other every day. (You can read more about Lyle and Erik’s daily routines here.)

Both are very aware of the Menendez supporters movement which exploded a year ago on social media.

Unfortunately, they don’t have internet access so the only videos or posts they have seen are those that were included in the 20/20 special that aired in April 2021.

You can watch parts of it on YouTube and the entire documentary is streaming on Hulu. It’s a recut of the Truth and Lies: The Menendez Brothers program from 2017 with ten minutes about the new supporters bookended at the opening and closing.

There are too many letters (!) so the brothers have been unable to respond to everybody.

Lyle asked me to thank all of their supporters for the letters and posts on TikTok and Instagram.

They’ve learned about what you’re posting through phone calls with their family and friends. BTW, there are two billion views of Menendez brothers videos on TikTok.

Lyle told me that the California Department of Corrections is considering a new program in 2022 which would give each prisoner a tablet for access to surfing online as well as email.

Most of our visit was spent talking about the habeas corpus petition which the brothers are hoping to file in 2022.

Lyle and Erik have exhausted all their state and federal appeals.

One potential piece of evidence that has never been presented in any court is the letter Erik wrote to his cousin Andy Cano in November 1988 complaining about the ongoing molestation by Jose Menendez, exposed in the final chapter of my book.

I have recently been going through hundreds of my taped interviews. They were originally recorded for note-taking purposes, and most of them were not transcribed. I’ve found new interviews with Lyle’s friends Donovan Goodreau and Glenn Stevens, as well as others, which could also become new evidence in the case. I told Lyle I was continuing the slow, methodical search through my tapes.

Our 90 minutes together passed quickly. As we hugged again to say goodbye, Lyle invited me to come back soon.

I’m planning to return next month.

More like this?

THERE’S A BOOK FOR THAT!